For millennia, the Arctic has been seen as a pristine, untouched wilderness. Yet, new archaeological evidence reveals that humans have been actively shaping this fragile ecosystem for at least 4,500 years. A recent study published in Antiquity demonstrates that ancient seafarers regularly traversed the treacherous waters of the High Arctic, influencing the development of one of the world’s most dynamic environments.

Early Arctic Settlers Were Skilled Navigators

The Kitsissut islands, a remote cluster between Greenland and Canada, have long been considered inaccessible to early humans. The surrounding seas are notoriously dangerous, even for modern vessels. However, excavations on Isbjørne Island and other locales within the archipelago reveal that people lived there as early as 2700 BCE. This discovery challenges previous assumptions that early Arctic inhabitants were land-bound, following migrating prey like musk oxen.

Researchers analyzed 297 archaeological features, including dwellings and artifacts, confirming regular travel between islands. According to Matthew Walls of the University of Calgary, who led the study, these journeys would have required “an incredible amount of navigational skill and ability,” given the unpredictable nature of Arctic waters. The lack of preserved boats in the record had previously obscured this seafaring reality, but the new findings solidify the evidence.

Humans and the Arctic Ecosystem: A Long Intertwined History

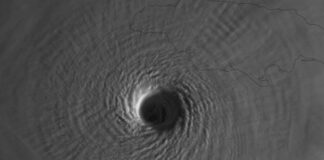

The timing of human arrival coincides with a critical period of environmental change: around 4,500 years ago, a significant portion of Arctic sea ice melted, creating polynyas—areas of open water surrounded by ice. This unfrozen water birthed a thriving ecosystem, attracting species like seabirds, polar bears, seals, and whales.

The study suggests that every species in this hotspot would have interacted with these early human settlers. This is not simply a case of humans arriving after the ecosystem developed; rather, human activity was an integral part of its formation. As Sofia Ribeiro of the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland notes, this history demonstrates that stewardship is not a modern concept but “something that has been happening…not isolated from the evolution of this ecosystem.”

Implications for Modern Conservation

Understanding the deep history of human-Arctic interaction has practical implications. Walls argues that archaeology can provide a “platform…to help better represent environmental histories that account for cultural stories.” The findings could inform decision-making by regional officials regarding environmental stewardship, ensuring future policies acknowledge the long-term role of humans in shaping the Arctic landscape.

The study highlights that the Arctic’s vulnerability is not just a recent phenomenon. Human impact has been woven into the ecosystem’s fabric for millennia, making an informed historical perspective crucial for effective conservation.