For decades, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) has served as the foundational text for psychiatry, dictating how mental illnesses are categorized, diagnosed, and treated. But this long-held “bible” of mental health is facing a critical re-evaluation. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is considering sweeping revisions that could fundamentally alter how psychological disorders are understood and addressed.

The DSM’s origins lie in a mid-20th-century effort to standardize psychiatric terminology. By 1980, with the release of the DSM-III, the number of recognized disorders had ballooned to nearly 300. This expansion solidified the DSM’s role as a guiding force in clinical practice, research, and even insurance billing. However, the manual has long been criticized for its lack of scientific rigor, with some arguing its categories don’t align with underlying biological reality.

The proposed changes aim to address these long-standing issues. The core problem is that the DSM’s current structure relies on distinct categories—major depressive disorder, bipolar I, post-traumatic stress disorder—while neuroscience and genetics increasingly suggest that these boundaries are artificial. While diagnoses may be reliable (multiple clinicians will often agree on them), they may not be valid (reflecting true underlying biological differences).

The APA’s proposed overhaul includes allowing clinicians greater flexibility in diagnosis. Instead of forcing a rigid label, doctors might describe a patient as experiencing “depression” without specifying the exact subtype. This could reduce the “laundry list” of diagnoses patients sometimes receive, which may not always be accurate. The revisions would also encourage doctors to incorporate contextual factors—such as homelessness or underlying medical conditions—into assessments.

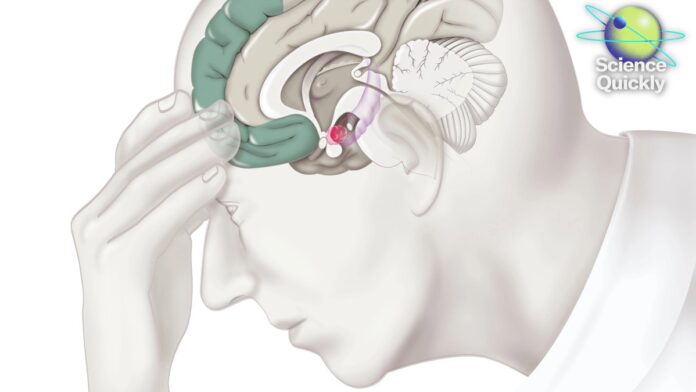

Perhaps the most ambitious idea is the inclusion of biomarkers: blood tests or brain scans that could theoretically reveal the physical basis of mental illness. However, this remains largely theoretical, as reliable biomarkers are currently lacking for most conditions. The only exception is Alzheimer’s, which straddles the line between psychiatry and neurology.

Experts remain skeptical. Critics argue that tinkering with the DSM’s structure won’t fix the fundamental issue: its reliance on subjective symptoms rather than objective biological markers. The gap between clinical presentation and underlying biology remains vast, and the hope of identifying clear genetic or neural signatures for specific disorders hasn’t materialized.

The DSM serves two key purposes: clinical treatment and scientific research. While researchers increasingly move away from rigid diagnostic categories to focus on broader symptom clusters, clinicians still need a system for diagnosis, billing, and effective patient care.

Despite the criticisms, dismantling the DSM is not a viable option. The system is too deeply embedded in healthcare infrastructure. The goal now is to find a balance between scientific validity and practical utility, a task that requires acknowledging the limitations of current knowledge while continuing to refine the diagnostic process.

Ultimately, the future of mental illness diagnosis lies in bridging the gap between subjective experience and objective reality, a challenge that will require ongoing research, critical evaluation, and a willingness to adapt as our understanding of the brain evolves.